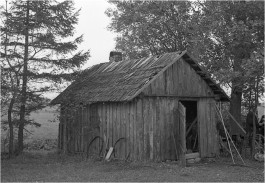

The volume contains 378 screenshots of benches found in real estate listings – from summer houses, homesteads, barns, garden houses, timber sheds to wash houses and saunas – in provinces and towns of Lithuania.

Of course, there is a principle to efficiently or effectively resist gravity. There are ways for local pine or birch to resist the shear, the bending, and time in general. Then, there is the benchmaker’s distance or proximity to the forest and use of its materials, which also imparts character and form on the bench. The bench is a marker of groundedness, hospitality, joy and care. And those meanings permeate location, both in terms of region and the spatial divisions of home. A woodworker, a housekeeper, hausmeister, or ūkvedys embodies knowledge in no worse or lesser way in making one. Benches are alive, spontaneous, sometimes excessive or stark, depending on the means of their makers.

This archival volume presents a variety of small wooden benches, without removing them from their usual spots nor forcing them into strict typologies. Most photographs are taken by realtors, some by the house owners or relatives. The houses and their benches are from peripheral villages and towns in Lithuania, listed on real estate sites costing “under 50,000 Euros”. These images capture life and the state of the house, the layers of refurbishments and updates, as well as the occasional cosmetic touches for their sale. In most cases, as you will see, it seems like life was removed quite recently, or not at all – the soup is still warm. Life is retained as it is and with benches in the margins. Bags, tools, blankets, apples, snow – the daily clutter of life – are found undisturbed. Each photograph gives many clues: the entrance bench is both private and common; the kitchen bench is both for work and pastime; the shed bench is for sunbathing and yard chores. They accompany the household and are as energetic, stubborn and capricious as horses, lambs, goats, and guardian dogs.

During printing preparations, the images were converted to grayscale, hoping this filter would help to train the eye to see the bench as more than an appendage to the dwellings. I arranged the benches in several sequences based on their similarity, mutability, and flow – a multifaceted quotidian subject swivelling around its vertical axis. This piece of furniture, freshly out of the workshop, or even more so if it is a decaying one, shows the elastic attachments to life and functionality.

Lithuania

Artbooks.lt, Vilnius

Sweden

Konst-ig, Stockholm

Finland

LYMY, Helsinki

United States of America

Topos, Ridgewood, NY

Bungee Space, New York, NY

Inga Books, Chicago, IL

Reading copies available

Finland

LYMY, Helsinki

Lithuania

Draugų vardai, Vilnius

ŠMC Skaitykla, Vilnius

NDG Dailės informacijos centras, Vilnius

Architektūros fondas, Vilnius

VDA Nidos meno kolonija, Nida

Šiaulių fotografijos muziejus, Šiauliai

Sweden

Konstfack Library, Hägarsten

United States of America

SVA Library, New York, NY

Now, that I am going over screenshots of benches, zoomed in and cropped from photographs taken by real estate agents and the relatives or owners of homes that are up for sale. I try to sort out, at least visually, the benches found in kitchens, main entrances, thresholds of hallways, greenhouses and pre-chambers of saunas. Unknowingly tracing some likeness back to the household members of the legged structures, usually with four sticks or two panels at either end and no backrest. They are idling, quietly awaiting labour, a feeling that permeates the boundaries of time. Benches here are simply tools and crutches built to paint the ceilings, kindle fire, wipe the noses of children, and peel potatoes. They accompany the household and are as energetic, stubborn and capricious as mules, lambs and baby goats. They were destined to have limp legs. Their hip joints are already slightly twisted.

I sit down and summon myself for a conversation about what I do with pleasure. Attempts to describe it lurch, uncontrollably. I cannot reach a satisfying aesthetic simplicity for any of these interpretations. So, when I observe my behaviour towards materials, I behave as a decomposer and transformer, because I don’t see anything in life in a sort of blank page way. I love to scrape and grind, and I like ambiguity. I tried to recreate and rebuild, not just mimic the benches I saw on real estate portals, from the houses they were used in. And step by step I built and hammered legs into planks and offcuts, materialising my internal topologies of stepping and sitting surfaces. I approach this structure as a carrier, a point of exchange, a haven, shelving actions. Of course, finding myself in such a workflow, stretching almost hysterically from the joy of learning to clumsiness, I became interested in noticing how we scratch brackets on processes that are so long. How do I know this is happening? And how I think and trick myself, and how that sooner or later fails to satisfy. Taking a cue from the mathematician and philosopher Alfred Whitehead, the advance of civilisation is better indicated by the amount of important operations performed without thinking about them, rather than the laborious intellectual scrutiny. I want to consider that remark on positivist, progressive, egalitarian and processual planes. The things we know are partial. It takes a lot of time, or in some cases courage, to sit with it personally, artistically and begin to see this more as an opportunity.

Thinking about the chain of production I returned to F.A. Hayek’s The Use of Knowledge in Society ①. Manufacturing and logistics are so tense in a fatigued pandemic market, that we ultimately seek decentralised ways of optimising and dispensing materials without needing to tell others what to do about it. As coupling and decoupling members of contemporary communities we genuinely expect some of the non-interference guarantees, as we personally have stakes, hopes and commitments to these economic clusters that we want to see succeed. So, the inefficiency of economic order that we deal with is not that it is irrational. The premise and set up of it is entirely rational, but the knowledge of resources and utilities is fragmented and scattered. That also results in ineclipsable partiality and contradictoriness. And as we go on talking about procurements, clear cuttings, subsidies, and the shredding of misplaced mountain pines, we talk about planning, and we talk about commons, we talk about living together. In Neringa, for example, the pines were like tall felted fences, acclimated sandstoppers, postal road guards that later became the cultural imprint of a coastal forest.

① Friedrich A. Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society’, American Economic Review, XXXV, No. 4; September 1945, https://www.econlib.org/library/Essays/hykKnw.html accessed 19 May 2021.

Architect and activist Yasmeen Lari, who worked for decades on disaster relief and housing projects for poverty stricken Pakistani villages, accentuated the financial feasibility and physical comfort of vernacular architecture. Her principles closely tie skills with the reinvigoration of the general financial status by making, selling and buying for themselves, rather than being invested in the globalist ideal of production for urbanites and the wealthy.

Something similar is highly noticeable in the language used around Lithuanian troba (a traditional wooden house). The building’s perimeter is called vainikas– a garland. The voids and entrances are not regarded as cutouts or holes. It’s the same with weaving, or basketry – these apertures are not something opposite or outside of the process. On the contrary, they are the process.

The term ‘scientific knowledge’ has a blind spot and a distaste for the knowledge of people, local resourcefulness and connections, which Hayek exaltedly describes as ‘special knowledge of circumstances of the fleeting moment not known to others’. The fascination with the grandness of things and a global cultural focus denies or avoids admitting how much of the local potential, and ultimately different needs, is omitted. This silent narrative of things that are small, liquid and quick to be put in secondary markets or uses, means that a lot of comfort, appreciation, dexterity and elegance gets overlooked and replaced with generic, industrial, uniform objects, as an extremely obvious example of the ‘Airbnb-ification’ of interiors, which grant seamless travel or even a home from home experience.

Then we return to the point that in a household, or in close proximity, ‘produced’ objects contain a fraction of specificity and robustness against globality. The surfaces retain high sensibilities: roughness, soundproofing, the modular partitioning of spaces. At the same time, we see how various planes of different aesthetics, affections and attachments spring out of this, and we compare and rant about it. Handmade, local, socioculturally integral or also in the broadest (even tackiest if you want) sense homemade objects are pressured to be both worthless and extremely precious. But they are calendars, hard drives – not made or comprehended in terms of efficiency – because in things, in matter, these transformations of attention, work and care rephrase themselves with each sitting.

This text is dedicated to my first bench and was a starting point for the upcoming body of work. The comparative study yet to be bound is looking into overlapping of craftsmanship and design as resilient artistic practices. The figure and structure of a bench becomes a metaphor to look into quotidian necessities, decorum and relationships between these value points in different regions.

Photographs of linden bench by Gedvilė Tamošiūnaitė.

Text was first published in Forest As A Journal, 2021

活动信息 书信息 本册包含378张在在立陶宛各省和城镇的房地产列表中发现的板凳截图:从避暑别墅、农场里的主宅、谷仓、花园房、木棚到洗衣房和桑拿浴室。 这本档案册展示了各种各样的小木凳。它们没有从环境中被独立出来,也没有被强行纳入某种严格的类型学。大多数照片由房地产商拍摄,也有些由屋主或亲属拍摄。这些在房地产网站上列出的价格“低于5万欧元”的房子和它们的板凳们都来自立陶宛的边缘村镇。这些图片记录了生活和房子的状态,层层整修和更新,以及为了将其出售才进行的外观修饰。正如你所见,在大多数情况下,生活气息似乎是最近才被移除的,或者根本就还没有:汤还是热的。生活被原封不动地保留下来,角落处的凳子也一同留下。包、工具、毯子、苹果、雪——生活中的日常杂物——都没有被打扰。每张照片都提供了许多线索:入口处的板凳既是私人的,也是公共的;厨房的板凳既是用来劳作的,也是消遣的;棚屋的板凳是用来晒太阳和做院子里的杂务的。它们伴随着家庭,像马、羊羔、山羊和看家犬一样精力充沛、固执而任性。 Monika Janulevičiūtė是立陶宛的设计师和艺术家。她的实践集中在当地性和剩余资源、学习结构、自我定义和适应性、以及和抽象社区之间的共同发展。对她来说,制作凳子中的直白和坦诚结合了设计、工艺和艺术实践。每张凳子都在选材、制作和用途的多样性中显示出对生活有弹性的附属。

以下这篇短文由Monika Janulevičiūtė写于疫情期间,2021年首次发表于立陶宛杂志FOREST AS A JOURNAL的第一期上。她将这篇文章献给她的第一张长凳。它是她即将展开的工作的起点。尚未完成的比较研究在探究工艺和设计的重合点,作为有韧性的艺术实践。长凳的形象和结构成为了一种隐喻,用来探究日常必需品、礼仪和这些价值在不同地区之间的关系。 现在,我正在翻阅经过放大和裁剪后的板凳截图。它们是来自房地产中介和待售房屋的业主或亲属拍摄的照片。我尝试至少从视觉角度对这些位于厨房、大门口、走廊的门槛、温室和桑拿浴室前厅中的板凳进行分类。不知不觉中,我从这些带腿的构造物身上觉察到一些如家庭成员般的特性,它们通常两端有四根棍子或两块板,且没有靠背。它们无所事事,静静地等待着劳动。这等待消弭了时间的边界。这些板凳是用来粉刷天花板、燃起柴火、给孩子擦鼻涕和削土豆皮的简单工具和支撑物。它们陪伴着家庭,像骡子、羔羊和小山羊一样精力充沛、顽固而任性。它们注定会有跛脚;髋关节也已经略微扭曲。 我坐下来,试着和自己探讨做什么样的事情使我感到真正愉悦;而想要对其进行叙述的种种尝试都不由自主地偏离正轨:我无法找到一种足以令我满意的审美上的简单解释。我将目光转向自己面对材料时倾向于分解和转化它们的那一面:我从不把生活中的任何事物看作一张孤立的白纸。我喜欢拼凑、钻研,也享受模棱两可。我想要重新创造和制作的不仅仅是那些我在房地产门户网站上看到的板凳的仿品。一步一步地,我在余料上敲琢为一块木板所打造的腿部,把我心里关于踏板和坐面的拓扑结构慢慢具象化。我把这个结构作为一个载体,一个交流点,一个踏实的落脚之处。自然而然地在这个工作过程中,我察觉到自己近乎夸张地从学习的喜悦跨越到笨拙感中,我的兴趣也迁移了:我们是如何在那些漫长的过程中度量、反思过程本身的。我是如何意识到这一切的发生的?我如何思考,如何引导自己,又如何或早或晚地意识到这一切注定无法使我满足。受数学家和哲学家阿尔弗雷德·怀特海(Alfred Whitehead)启发,文明的进步更多归功于不假思索的大胆行动,而不是小廉曲谨地反复思忖。我想在实证主义、进步主义、平等主义和过程性的发展阶段上考虑这一言论。我们所知道的事情(知识)是片面的。而去认识、了解任何事都需要大量的时间——甚至在某些情况下需要勇气——亲自坐在那里,从艺术角度出发把它看作一个机会。 在思考生产链时,我回归到弗里德里希·哈耶克 (F.A. Hayek) 所撰写的《知识在社会中的运用》 (The Use of Knowledge in Society) 一文。制造和物流在受疫情影响的疲乏市场中显得尤为紧张,我们从根本上寻求去中心化的方式来充分分配和利用物资,如何对其进行利用的指导则显得多余。作为在当代社群中彼此作用、互相影响又相对独立的个体,我们真正期待的是一些不受限的自由,因为我们个人对建立在这些社群基础上的的商业集群有付出、期许和责任。因此,我们所面对的经济秩序中的低效问题并非情理之外:它的前提和设定是完全合理的,真正的问题在于对资源和公用事业的理解零散且分散,也正是同样的原因导致了难以遏制的不公和矛盾。而当我们继续谈论采购、皆伐、补贴和砍伐种错了位置的山松时,我们谈论的是规划;我们谈论公地时,谈论的是共生。在内林加(位于立陶宛最西部,毗邻波罗的海,是立陶宛最小且人口最少的市镇。其名来源于一门已消亡的波罗的语的单词nerija,意为长形的半岛沙嘴),同样的松树就像高大的、带着厚厚屏障的栅栏,它是生存能力强的阻沙器、邮政道路的卫士,成为沿海森林的文化印记。 建筑师和社会活动家雅斯敏盖瑞·拉里 (Yasmeen Lari) 在过去几十年间一直致力于巴基斯坦贫困村庄的救灾和住房项目,她强调乡土建筑的经济可行性和身体舒适性。她的原则是将技能与重振财务状况紧密结合起来,为自己制造、销售和购买,而不是投入到为城市人和富人建设全球主义理想中。 类似的表达出现在描述立陶宛的troba(一种传统的木制房屋)周围所使用的语言中。建筑物的周边被称为vainikas——一个花环。空隙和入口并没有被理解为切口或空缺。这与纺织或编制篮子一脉相承——这些孔隙并不与编织的结果对立,或处在制作过程之外。相反,它们就是这个过程。 “科学知识”一词刻意地蔑视那些来自人民群众的知识、地方性的应变能力和关系网络,而哈耶克恰恰把这些誉为 “关于难以察觉的、转瞬即逝的情况的特殊知识,”即有关特定时间和地点的知识。对宏大叙事和全球文化焦点的迷恋导致对地区潜力,及其随之而来的种种需求被否定或质疑,最终被彻底遗忘。当这些小的、流动的、很快投入二级市场或使用的事物只有悄无声息的记载,很多舒适、欣赏、灵巧和优雅之处随之被忽略,进而被通用的、工业的、统一的物体取而代之;想想室内的 “Airbnb化",它提供了从家到“家”、甚至与家对等的旅行体验。 让我们回到这一点上:在家庭或近似的环境中所“生产的”物体自带一小部分特殊性和茁壮根植于自身的反全球主义性。它们的表层反映对周遭环境的高度敏感:粗糙,隔音,对空间实现模块化的分区。同时,不同的美学、情感、和喜爱之情从中层层涌现,而我们对此进行比较和漫谈。手工制作的、当地的、社会文化上集成的或也是最广泛的(甚至最俗气的)意义上的自制物品被挤压得既没有价值又极其珍贵。但它们是记事历,硬盘——既不是为了提高效率而制造的,也不是从这一角度被解读的——因为每一次坐下都意味着手头的工作、所关注的事情在发生转变和重新表述。

Monika Janulevičiūtė is a Lithuanian designer and artist. Bench-making for her binds design, craft and art practices together. They become frank, integral and quotidian. Each bench ripples through varieties of material choices, skills and uses – showing an elastic attachment to life. It accompanies the observer and is as energetic, stubborn and capricious as a mule, stray cat, goat or guardian dog.

All rights reserved

2023